Oyako Day Essay Contest 2018 Winners

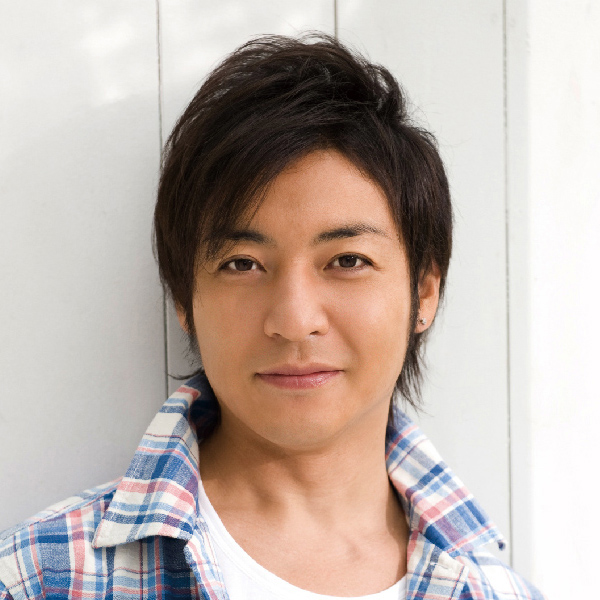

GRAND Prize

In my second year of junior high, I had a fight with one of my classmates and got in trouble because I hurt him. At the time, I was in the middle of a relapse into adolescent revolt. But, since I was also defending some friends this classmate had bullied, I thought I had done the right thing and didn’t have any second thoughts about it. As it was, I wasn’t taken to the teachers room to discuss how the incident occurred. I was immediately given sole blame for the injury. When I kicked up a storm about how he’d bullied my friends and why wasn’t he getting into trouble, they asked my father to come to the school.

I left school with my father. He hurried me along to the taxi stand and into a cab, then we headed straight to my classmate’s house. Once on our way, he turned to me and patiently asked, “And you, what do you think of all this?” I explained the whole story and energetically defended my part in it. My father murmured, “Really.. I see” and fell into silence. His silence lasted just the five minutes till we arrived, but I remember feeling they were the longest five minutes I’d ever known.

Once at the house we rang the intercom and someone yanked the door open. It was my classmate’s father. He questioned me closely on the extant of his child’s injury and whose responsibility it was. My classmate didn’t seem to be around.

When he stopped bombarding me with questions for a moment, my father stepped in and said, “My son says that he had legitimate reason to quarrel with your son. As his parent, I believe him. But, also as a parent, I must apologize to you for the injury done to your son. I will pay for any medical care that’s needed,” and bowed to him in silence. Then, turning his back to the house, he whispered in a small, dry voice, “We’re going home.” On the way home in the taxi my father’s regard was full of gentleness. There was never so much as a word of blame. When I looked at him, I had the feeling that his shoulders had never looked so broad. My father, as a parent had stood by me and taken responsibility for my actions. At that very moment, my adolescent revolt came to an end.

OTICON Prize

Soon you’ll be six years old ! When you were at the Kindergarten, you got good at drawing and would bring your drawings home. My favorite was one of us holding hands with big smiles on our faces. It’s a comfort to think that we were happy then.

You’re so bright. You probably already know why your Mother and Father don’t live together. We talked about what went on at our house a lot before we left, when you were four and we’d just come back from the shelter. You remembered so much I was surprised. It must have been hard for you, but thank you for coming with me. I promise we’ll be happy.

There are both happy and painful things in life. In happiness, we feel like the sun is shining on us and we’re full of energy. When things are painful, we move into shadow. It’s dark, and we feel weak. Back in our old house, we slipped imperceptibly into the dark and barely ever saw the sun again. I was so ashamed, all I could do was cry. When I did, you would bring me a towel to hearten me or line up your toys to play with me. It was moving to see how adult you acted.

The world is wide and full of wonderful things. I want you to enjoy them, innocently as a child, laughing without guile. That’s why I took you out from the little world without sun where we were trapped.

Up till now, I’ve put you through things no child needs to go through. So from now on, I’d like to think we’re going to enjoy things to the full.

If you look at flowers and insects, you know that even the smallest plants and animals have life and for all we know, a heart. I want you to know that it’s OK to play with those younger than you, and that you should take special care for those who are smaller and weaker than you are. Learn as much as you can and grow up quick and strong. Watching you grow tells me how good it is to have you here.

Let’s be close, enjoy everything that is out there and take on the world, wherever it leads us.

I’ve committed crimes.

I could say that it was just to get by, but it’s still a devastating failure.

And then, I’ve lost so many things. Compared with all the many things I have lost, I’ve gained little. Or maybe I’ve just gained nothing at all. Whichever it is, I can’t recall any single thing that I’ve gotten.

In detention, I massaged backs inscribed with tattoos of Dragons and Thunder Gods, participated in prison athletic meets, drank Cola, and peeled potatoes day after day.

One day, I noticed that my second decade had ended.

And then I knew I was stupid.

But, however dumb I’ve been, my parents didn’t drop me.

No, even in face of what I was, they were still there.

No matter what I’d done, I was still the life they had given birth to, a blessing.

Even before they might even begin to wonder whether I was good or bad, my parent’s premise was that I was everything to them.

My relation with my parents hasn’t changed.

In other words, our relation is much the same as when I was 18 years old. We’re just an ordinary family with the usual kind of relations, not particularly clingy, but we get along.

These days I have a job, live an ordinary life and speak to my parents as an adult. All of this I owe to my parents.

My parents trust me.

My parents forgive all my faults unconditionally.

For them, I am irreplaceable.

This is what I have learned over the last ten years.

This is not about gratitude or apologies.

I may be dumb but I am going to try to live.

I have no desire for death. Not at all.

I still have things I want to do.

But not for my parents. This needs to be for me.

It’s about effort.

Taking the discouragement.

Fighting for something.

Nonetheless, when I get to where I want to be, the very first people whom I’ll tell will be my parents.

I will carry on.

I will carry on with them in mind.

Now, the two of them let me do as I please, something for which I am so grateful.

One day, I hope to fulfill my dreams, stand before them and say “What do you think !!”

I went back home on my winter break and got caught up in year-end cleaning. It was my job to clean up the storeroom. While straightening up the shelves, I discovered an old photo album. The front cover was thick and covered with so much dust I thought the album must have some strange attractive power. Pictures: my Grandmother cradling my mother at the hospital, my mother standing shyly in front of the school’s front entrance in a sailor suit, one from the height of the bubble economy, a shot from abroad when she was traveling after graduation. All the pictures were of my mother, taken long before I was born.

Just as I was closing the album, full of feelings about my secret glimpse into my mother’s past, I was brought up short by the realization that this woman I had always seen uniquely as my Mother had also been a baby, a little girl, a child… I was frozen stock-still by this fundamentally obvious discovery. It wasn’t until the moment I took form in my Mother’s belly that she had become a Mother. Even when you were frustrated because things hadn’t gone well, exhausted from caring for my Grandmother, or wounded by words of sharp criticism, you carried on in your role of mother, always full of tenderness and without missing a beat.

I wondered if I could ever manage the same feat. Suddenly, simply carrying on day after day as a Mother struck me as being an incredible thing. And all at once, I was seized by anxiety, ran from the storage room and burst into the kitchen, which was full of the familiar smell of my mother’s curry.

“Mama. You’ve always been there for me. Someday, I hope I can be as good a mother as you are !”

Standing in front of her, I felt as if I’d shrunken in size. When she gave me a hug, I think I got even smaller.

My mother gave me a puzzled look and said, “You grow into motherhood laughing and crying along with your children. I’m still way behind your Grandmother though !” and laughed wholeheartedly.

MITSUBISHI ESTATE – SIMON Prize

“Hey You ! You’re eyes are puffy. Have you been crying !?”

My classmate Terada cried it out loud and clear our senior year of High School, just before our graduation ceremony.

After elementary school, I got into an escalator school, so my mother made my lunch boxes for 6 years running. These were lunch boxes with two levels in them. You could say they hoisted me up with both hands. The lower level was filled with white rice with a single pickled plum right in the middle. The second level was some kind of dish, not leftovers from dinner or breakfast but prepared fresh by my mother every day.

Since there weren’t any microwave ovens for us at school, I ate my lunchbox meals cold everyday. Even cold they were delicious, eve-ry-day.

They say adolescence can be cruel. On the rare occasions when I had to resort to a bought lunch, I was happy. When my mother slept late, I always had 500 yen to use at the convenience store where I’d buy some bread or a CalorieMate. I was quite satisfied by these rare bought lunches, but it had nothing to do with being tired of my mother’s food.

The day my eyes were swollen with tears was a winter day in my final year of High School. It was the last day I’d be bringing my lunch box to school. At the thought of trading my Mother’s lunches for all the bought lunches to come, however much I liked them, I cried before leaving the house. After all those days of having my Mother’s carefully prepared lunches at my side, today would be the last. My heart sank for all of the times my Mother had handed me my lunch and I had not put my thanks into words, 1566 Thank-You’s. And my Mother cried too.

At school when I looked inside my lunchbox, I thought I was going to cry again. What my Mother had prepared wasn’t especially luxurious. But, I’ll tell you: asparagus wrapped in thin slices of grilled meat and eggs with scallions, my all-out favorites.

Thirteen years later and I still remember the pain I felt in my chest, like someone had given my heart a sharp pinch. These days, my Mother makes a lunch for herself everyday to take to work. When she reaches retirement, I’m thinking it’ll be my turn to make lunches for her.

My Mother started making preparations for her funeral about a year ago. It was just the week after my wedding. Once back from my honeymoon, I was immediately summoned to her house to hear her testament directly. Since I’d finally left home, maybe she thought that things being settled would be a relief to me. My father had already passed away. My mother’s child-bearing was late, and she was now past seventy. She told me she wanted to live as she pleased during her remaining years, and her plans seemed well thought out. Nonetheless, I couldn’t get used to the term, Final Arrangements, and hearing it from my Mother was like a thunderclap. I was speechless. I just stared at my mother’s aged face.

After a month of preparation, my mother went into action. First she sold off her house and property. She moved to a rental apartment with a garage. Between the money from the sale of her property and the pension benefits coming to her, she could put money aside to cover her funeral and still have enough to live a full life. Once she’d finished arranging her personal finances, she traded her car in for a fuel efficient hybrid and started her travels. She’d lived in Kyushu for years and began by visiting each of its prefectures, then made outings throughout the San’in Region and Shikoku. My mother did all the driving. My only contribution to this part of her funeral arrangements was to sometimes tag along.

My Mother, the driver, looked healthier than ever. From the passenger seat, I asked her how her health was, whether she had any complaints. She said, keeping her eyes on the car in front of us, “No, not right now.” Once on the speedway, she got into the fast lane while occasionally weaving from one lane to another to get ahead. From the looks of things, she was healthy. “I’ll be a bedridden invalid soon enough. For the moment, I just want to do as I please.” She stifled a laugh while she said this. Once at our destination, my mother, not to be outdone by the other tourists, proved an avid photographer, shooting multiple photographs while moving with the agility of a child.

My mother’s final arrangements are still ongoing as of this day. Recently, she took a plane from Kagoshima to Okinawa. Since she handed in her driver’s license, I’ve sometimes taken over the wheel. In the long run, I haven’t been able to get used to my mother’s new life. However, when I see my mother’s laughing face go off on another journey, it’s true that I feel in my heart that she’s being rewarded for many years of generosity.

I call my Father “Otō”. It keeps a little of the formality of “Otō-san,” without the familiarity of “Papa.” It seemed to fit our circumstances, and it’s what I’ve called him since I came of age. My Father doesn’t intimidate me. I’ve never sought his advice about my studies or progress nor has he questioned my decisions. He neither approves nor obstructs the things I want to do. When I’m with him, I tend to talk about silly things that I am not even sure my father understands, but he’s there with me, tagging along with nods and sighs, and were at ease together. But basically, what I ended up thinking was that my Father wasn’t particularly interested in what I was doing.

The first time I lived separately from my parents for any length of time was during my third year of college. That was when I left for a year abroad. My whole family went with me to the airport to send me off. It seems that after I went through the boarding gate, my mother and younger sister started to leave but my Father said he was staying until my plane was out of sight and remained to watch my takeoff. My Father’s never talked to me like a parent. This was the first time I knew that he worried about his daughter. Now I’ve left my hometown and live in Tokyo. Whenever I get a long vacation, I go home to visit, and when it’s time to go back to Tokyo, it’s always my father who takes me to the station. For a long time, he would watch from the train crossing until my train disappeared in the distance. These days he accompanies me through the ticket gate and sees me to the platform. We separate at the boarding zone or sometimes in the train. There’ve been no tears. Yet, when he finally says that last “See you soon,” maybe it’s because I’m right next to him, because I seem to hear everything he’s not saying, and I just cant hold back my own tears.

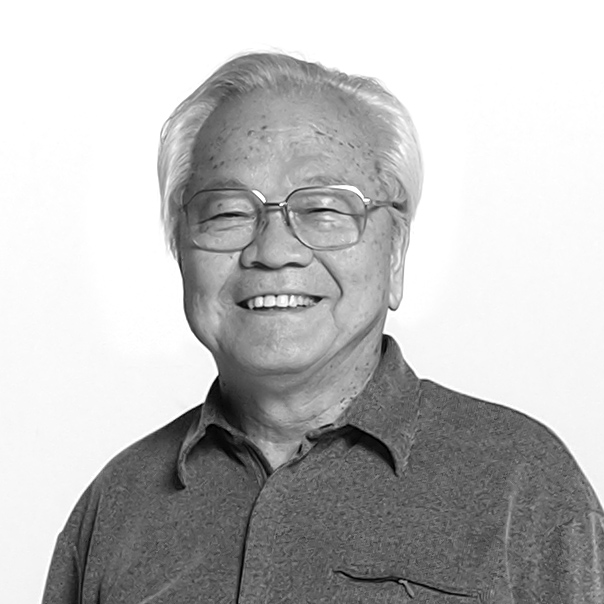

MAINICHI NEWSPAPER Prize

I was never able to know much about my father’s life. Our relation was never a very good one.

Both my parents are well. My Father must have been a little older when he got married than we’d expect these days since he’s 40 years my senior. He was an academic. As an academic, he was extremely logical in his thinking as well as diligent. Further, he was quite proper, to the point that a child’s play was painful for him. Or was it simply a nuisance because it disturbed his research. At any rate, I was scolded and kept away from him. From the time I was very young, I knew only my mother.

Just a few years ago, I had some real trouble, the kind of incident that most people never experience. It was also the first time I saw my father fly into a fury. He wasn’t in a rage about me. It was about the incredible damage being done to me. The way my father looked at the time, his determination and concern, gave me the courage to face the situation I was in.

The details of what happened to me are of little importance. I retain only my Father’s resolve in defending me, which made me wish that I had been more docile earlier, that I had been able to speak with my father from an earlier age. Then, perhaps I would have had a more fulfilling childhood. Later, when I finally dared confess these sentiments to my Father who was already in retirement at the time, his answer surprised me.

“Your Father thinks the same thing, but also that it is not too late. We can start now. And because we can do it now, we should. There’s nothing late about beginnings. We still have time to talk about many things.”

Perhaps my Father had finally realized just how much I desired his love. Whatever the facts of our past as parent and child had been, they now just looked like moments of brief embarrassment. However much they separated us or brought us together, I understand their true nature now, when I am overwhelmed by their tenderness.

I grew up with only my mother. When I was in ninth grade, I became anorexic. Excessive exercise along with the limits of my food intake made me so skinny that I finally withdrew from school during high school. I was also hospitalized. My mother never reproached me. She continued to prepare elaborate meals for me.

This went on for four years.

Finally, when my body was overwhelmed and I was spending my days lying in my room, my mother confronted me, and for the first time ever, she actually hit me.

She said, “Please open your eyes and see just how we are blessed in our lives. Being alive is not just a matter of course. The fact that there are families. The fact that you have a family. We are here today because our ancestors came before us. They have given us this life, and you should live it.”

As I lay there watching my mother’s recede down the hall, I thought about just how much I had always disparaged myself. That I’d be better off dead, that I was weak: how many times had I said that to myself. How many times did I compare myself to others and find them better, stronger. It’s only normal that I saw everyone around me as stronger. Each and every one of them was filled with confidence and busy with their lives. Since they all looked down on me, I never made an effort. It’s as simple as that.

“You should live. No matter how weak, no matter how puny. Be confident and live !”

The moment I finally heard that, I felt my heart take wings.

So much for anorexic me: one slap and a mother’s words.

I’ll remember those words for the rest of my life.

They saved me from the morass of anorexia.

And I’d like to say this to any others who suffer from eating disorders like I did, “You should live !”

These days my mother and I laugh about my time as an anorexic, as long as it was.

Yes, it was long, but now I’m living and it’s good.

Because being alive is real happiness.

That day, I was in sixth grade, and it was the first time I’d ever failed a test.

I was on my way home after they’d announced results for the junior-high entrance exams.

“I’d like to walk to a different station,” I said to my Father who was at my side. I’d just said it on the spur of the moment, but it brought home the extremity of my situation. In fact, that station was the quickest way home, so I guess I just didn’t want to get on a train.

We walked for about an hour, got on a train at a station where there’d be no one I knew and went home. When we opened the door, something smelled really good: deep-fried food with curry rice, my favorite. When I got to the dinner table, I saw a selection of batter-fried appetizers crowned with a pork cutlet, all of it laid out across curry rice.

No matter how much I liked all of these things, putting them all together in one plate seemed a little extravagant.

My mother was a good cook who specialized in filling the table with my favorite dishes, one after the other. As usual, sitting at the table and watching my mother prepare things, my nose was seized by a crowd of pungent odors.

I ate as if in a dream.

I used my spoon to scoop up as much curry as I could. I wolfed down the selection of fried foods.

I ate and ate, but there always seemed to be more.

When I looked, my plate was still full of my favorite foods.

When I thought about, I realized that this’d been the way it always was.

When I lied to my friends about being able to do a back hip circle on the horizontal bar, I ended up coming home crying, and just like today, my Mother made heaps of my favorite foods.

“This is the quickest way to feel better !”

That’s what I always think when I dig in, and soon enough, I get taken in by my favorite foods. Even though I know my mother’s secret agenda by heart, I get taken in by the food every time. The night after I failed a test I thought could never fix, I energetically cleaned my plate and went to my room for a deep sleep.

“Whatever happens, you’ll feel better after you eat !”

My mother taught me that. Time-tested, the ultimate strategy.

TSUBURAYA PRO Prize

“It’s not working.” I’ve thought that again and again.

I’ve been fighting illness for almost ten years. There was a time when I could walk by myself, but between the ebb and flow of my strength, I gradually came to be bedridden. Just when I get to the point where I think I can recover, the disease pushes back even stronger. “Two steps back for every one step forward” marks my days.

With both body and spirit in the grip of this disease, it wasn’t the time to be making plans for rehabilitation. The weakness and pain when illness suddenly sweeps in to attack… Somehow my condition had become a barrier: it was back to bed and my fight with pain. When we began rehabilitation again, time had passed mercilessly on, my body was even weaker than before. We’ve fallen into a vicious cycle where each succeeding session of rehabilitation demands less and less of my body.

“Why doesn’t my body respond…”

At night, unconsciously, I give vent to my feelings in soliloquies that only I myself can hear. And hearing myself, I cry, and then go on wrenching tears from my withered eyelids. “This is all too much…” I lose myself in my grief as if in a sea of trees. With the strength gone from my body, I’m trapped in darkness, followed by loss of consciousness.

Suddenly coming back to myself, I can see that the sky beginning to lighten. Looking around me, the morning sun shines around the edges of the curtains. From my bed, I see a photograph of two people.

One is my oldest son, now seven. Forthright and of large build, he’s smiling like Ebisu amongst the Seven Gods of Good Fortune. I can hear his cheers of encouragement in my heart, “Papa, Get strong !” The other person is my funny, little, four-year-old son. He’s had the same face since he was one, no matter how many times we photograph him, a face like a full-smile emoji. He doesn’t know the least thing about the mess I’m in. He’s posing as a hero in the photo, full power on. I stare at their photos for a moment. “Why?” I blurt out.

Children have a strange power. Soothed by the charming photo of my two sons, a ray of light breaks through my troubled heart, and just as quickly I find myself thinking, “Today. Let’s get on with this fight over my destiny”

TSUTAYA Prize

The title was “God’s letter.”

I remember the penciled characters written in her unsteady hand.

It was a composition by my nine-year old daughter.

It wasn’t schoolwork. It was about a God who spoke to a little girl. There were no pictures, only characters, a short story of about 10 pages.

When I’d read it I asked my daughter whether she’d seen it on television or got it from a picture book.

“I made it up,” she replied in a small voice.

“Really,” I answered and picked it up to read it again.

We’ve lost the manuscript, but I haven’t forgotten the story.

“God is always looking at you”, “Where is he? On top of the clouds.”, “No, that’s not it. God’s in your heart.”, “In our hearts?”, “When times are hard, happy or when you don’t understand; you think God is there. You believe strongly that I am in your heart.”

Three months before this story was written, my daughter’s mother left our home.

To be more precise, I sent my wife away.

I didn’t explain the reasons for this to my daughters.

My younger daughter was two and a half, and she cried every night.

My elder daughter hasn’t cried since the night before her mother left.

I’ve realized that this was out of consideration for me.

I wondered if her mind was sound or unsound.

I felt sorry for her.

I thought she must be trying to make me understand something.

I tried to decode her intentions but couldn’t.

We hadn’t seen any nights of endless tears for more than five years.

Our situation wasn’t going to change, we could only accept it: no one had the answer to this puzzle. No one had a way out of this maze.

Had she written this story of a God who controls our destiny to fulfill some pressing need? As her father, as the husband who had decided on divorce, as someone who lived with her, I worried over what I should or could do.

After a while though, I stopped thinking about it.

When it comes from a child, guidance, instruction and remonstrations look more like impudence. We may be Father and Daughter, but we’re very different people. It is difficult to blindly accept that your daughter is imbued with a nobility that goes beyond the common lot. And yet, my daughter is blessed with unfailing optimism, the strength to communicate it as well as thoughtfulness towards her family, and I believe my daughter’s strengths are her own. I’ve come to understand that the acceptance of guidance, obedience and support are part of a parent’s role.

My daughter taught me this, and I’m grateful.

OYAKO DAY Prize

I was a child who liked it when my Mother tucked me in, so much so that I sometimes kicked my covers off just to see if my mother’d come back. I liked the fluffy feel of my quilt round my chin when she said goodnight, and rediscovering the softness of my blankets when I woke from slumber. In addition, when I rolled over and someone fixed my blankets for me, I loved the afterglow of warmth that filled them. Why did I like all that? Not just because of the warmth. But because that warmth carried my mother’s love with it.

Now that I’ve grown up, my mother no longer tucks me in, but when I fall asleep, I always remember her.

“Don’t catch a chill and get a cold”, “Now look how you’ve uncovered yourself again”: the things she said to me when I was little, the words that showed her concern and a parent’s selfless love. I feel a slight tingling and know that if I lower my guard, I will burst out in tears. The heart swells with the memories of all the days gone by, never to come again.

I can’t really remember the feel or warmth of my quilt that precisely now, only the deep peace I felt when my mother tucked me in remains clear. It is the memory of my mother’s love for me.

These emotions were lived long ago. One day, I would like to feel what my mother felt. Because it’s certain to be a different way of looking at the world.

私は下手な短歌を詠むが、自ずと家族のことを詠んだ歌も出来る。そんな中で、全国的に著明な短歌大会で、特選に選んで貰った歌がある。それは、

頼まれもせぬ孫の名をあれこれと日がな一日考えておる

である。長女には、結婚後直ぐに子供(初孫)が生まれたが、長男にはなかなか出来なかった。下手をすれば、我が家の名字「赤松」の継承も終わりかなと思っていた。本人達も随分と苦労したようで、最後は人工授精に頼ることにしたが、その甲斐あって、同い年の夫婦がアラフォーに近付いた時に、やっと男児を授かったのである。

先の短歌は、その孫が生まれる直前に詠んだものである。頼まれてもいないのに、もし自分だったらどう命名するかと、落ち着きのない状態を詠んだ。結局、命名は夫婦二人で、『蓮太郎』となった。本籍のある大分県の偉人、「瀧廉太郎」を意識した命名である。暫く後にお祝いに訪れた際の、私のお祝いの歌は、

命名は蓮太郎なりふるさとの偉人に似たる佳き名と思う

である。

我が赤松家は、男ばかり五人の兄弟がおり、それぞれ二人ずつの子供を設けたが、その内男子は六人いるのに、孫の男児は僅か三人である。一人は養子なので実質二人である。辛うじて二人が、「赤松」の家系を繋いだ。その内の一人が我が家だ。

わが子を詠んだ最初の歌は、

諭吉をば二分の一にしたる程なればいいぞと諭と名付く

である。後に、故郷中津市の賢人、「福沢諭吉」の人物の大きさを知るに付け、二分の一でも誠に恐れ多い命名であったかと、思った次第である。長女に関する思い出深い歌の一つは、

爪摘めと詰め寄り来たる幼子の爪摘むことは危うかりけり

である。二人の子供を同時に詠んだ歌もある。

父の観る銭形平次にチャンネルを合わせて子等は飛び出して来る

毎日8時過ぎに帰宅する私の車の音を聞き分けて、迎えに飛び出して来ていた。そんな健気な時期のあった子供達も、今はもう40代。当時の私の年代を越えてしまった。

When I was in my third year of college, my father suddenly left our home. Since the time that he left, I can only remember one time when we went out and ate dinner together. On our way home, I got off the train first, and he turned to me and said,

“Let’s eat together again.”

“Yea, let’s do that !” I answered, and heartily waved goodbye.

A promise with a reticent and bungling father, and that was the end of it. I didn’t hear from him again, and soon enough I forgot the promise. I just thought I’d meet him some other time. Time went on. I graduated from High School and got a job. Eight years had passed since I’d last seen my father. I was 28.

In 2017, I found out that my father was in the hospital with cancer. It was just after the New Year. We all thought that he would be cured by surgery, but in the end there were complications and my father did not recover. This was not the kind of reunion I had hoped for, so full of tears and regret. The day after my father passed away, I dreamed of him. I saw my father again and again as he was before his death. It was a really good dream. I wish I could have recorded it so I could see it again. I was eating out with my Father. The name of the restaurant was Good Fortune. Maybe it was a place in Heaven? It was Showa-style cozy and elegant. It seemed to me like a place my father liked. The food was family style and all of it good. I was surprised by how my father was wolfing it down. But when I said to my father, “We should come here again !!” I immediately woke up. I think my father must have remembered that old promise. We were eating together just like we had been the time we’d met so long ago. I could no longer meet my Father in this world, but in my dreams, we could meet as often as we liked. This is what my Father showed me. Up until my Father died there was no end of things I was sad about, but when I awoke from my dream, I’d found something to smile over.

“Really, when’s it going to get hot !…” I’d just gotten home and this is what my father had to say. We’d been breaking 30℃ for days on end. My father had a lot of errands outside the house, so I supposed he was talking about the intense heat.

“E—v, ev, ev, every, body—and Ryōji, le-t’s-get-together !!” It was some years ago that my father’s stories had made my four younger sister’s and I gasp. When we’d insist that he read us a bedtime story, it was never a picture book but always his own stories he insisted we listen to. We’d heard glittering tales of his growing up in a valley in Yamanashi and why heat didn’t bother him. How during summer vacations he’d chased cicadas together with a friend of the family named Ryōji. How they’d escape the blazing sun by going off on their bikes to a distant pool. And no hesitation about serving up the same summer stories in winter, they were good all year round.

For my father, the summer vacations during his elementary school years were incomparable. He didn’t just tell us about them. He would take all five of us to the local park on weekends. He led us everywhere, only too happy to run, but he’d get too excited and Mom would get mad.

When I think back on it now, from the time I graduated to the later grades of elementary school till today, I haven’t heard Father’s stories. He mostly talks about school exams or job hunting, things that are happening right before his eyes. When the summer heat’s on, rather than going out to the park or the pool, he mostly just spends his time at home these days. The two of us daughters who are still at home, as well as our father, are all getting older: we all prefer being home with the cooler to being out under the sun.

I’m in my fourth year of college, so next spring I will be leaving home to start a new job. I’m not really at a stage in life where I’m thirsty for tales from “Neverland”. But let’s get Dad to tell us “stories about Summer” next Sunday. I’m sure that he’s still ready to tell about the cicadas he got with ol’ Ryoji. It’d be a pleasure to forget this hot, sticky summer for one that was fun. Though still a bit embarrassing.

“The day you were born, we were eating curry and watching Sazae-san on television.”

My whole life, I’ve had to listen to this portrayal from my mother. Is that why I’ve grown up to love curry and gone on to record succeeding episodes of Sazae-san?

Once on the subject of the day I was born, my mother always ends up with the following:

“So there’s no doubt you were born on a Sunday. Children born on a Sunday are always lucky !!”

Really, I should be thankful for this story, because it made me believe in my own good fortune. When confronting my college entrance exams and later, job interviews, my mother’s story always bolstered my courage. Though, to tell the truth, I failed my entrance exams.

Then one day, when I had time and didn’t know what to do with myself, I checked my smartphone for a calendar of the year I was born and discovered, to my utter surprise, that I was born on a Saturday. That explained my college entrance exams as well as the number of times I’d been turned down for jobs: it was inevitable.

Straightaway, I asked her what was going on. Why hide the truth about my day of birth?

But, as usual, my mother just went on, “We were eating curry and watching Sazae-san.”

Set aside the curry, wasn’t she replacing one memory with another just like Sazae-san herself might? Of course, everybody knows that a really long time ago Sazae-san was programmed on Tuesdays. But the problem here was Saturdays.

I thought of episodes of Sazae-san that I’d gotten relatives to record for me. No one had been that kind of fan before then. Just about the only thing left for me to do now was to question the veracity of my papers. Rather than Sazae-san’s broadcast suddenly shifting to Saturday for a day, it was easier to believe that some busy intern had miswritten his entries. Or perhaps, seeing Sazae-san was just some nightmare inspired by my mother’s labor pains.

As of now, the stories that so inspired my confidence for more than 20 years are nothing but a headache, not even worth talking about.

When I think about this, I get so downcast that I just loose it.

Well, for starters, let’s eat curry for dinner tonight…