Oyako Day Essay Contest 2024 Winners

Event period: May 1st to August 31th, 2024

Event location: Instagram and email

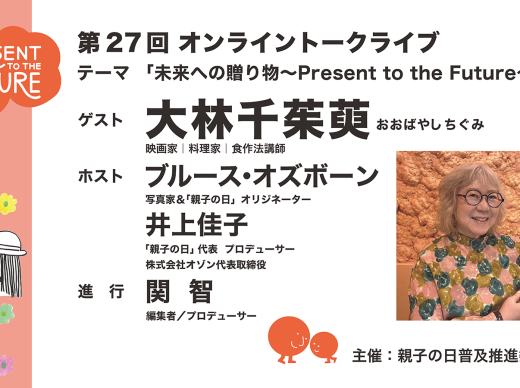

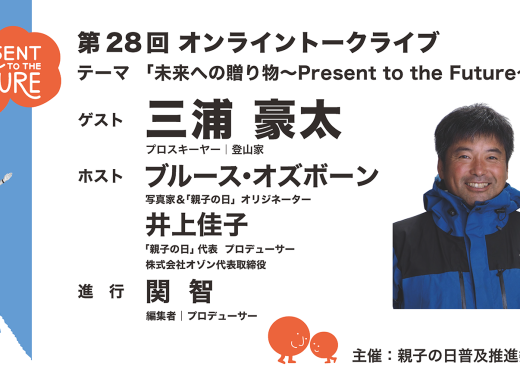

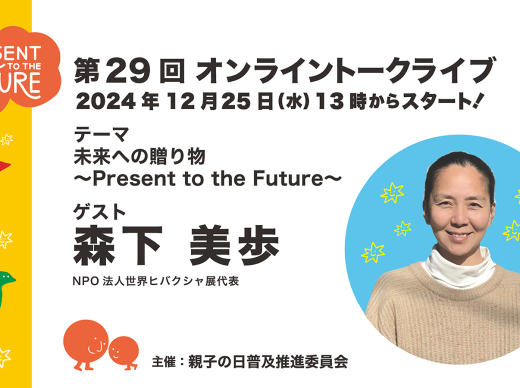

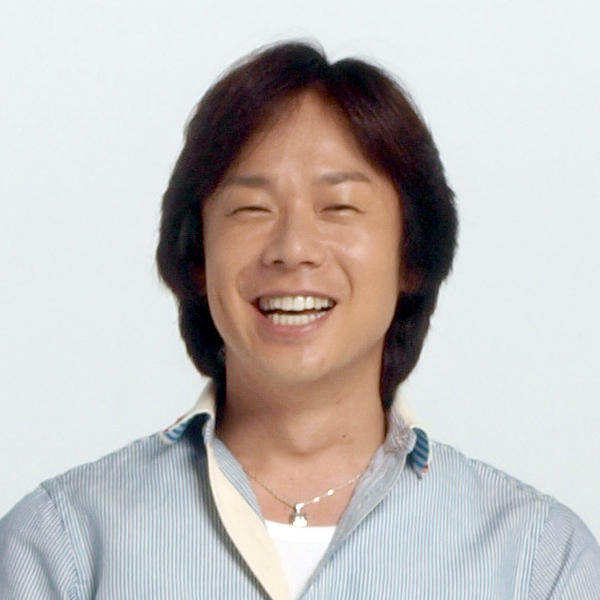

OYAKO DAY Special Prize

- Kaohagan Quilt Rug and “Taisetsuna Mono” Photo Book

I started writing lyrics as a hobby and began posting them on a songwriting website that existed at the time. Around then, my daughter was in her last year of kindergarten. She would take the enka or pop songs I wrote and make up melodies on her own to sing them.

Then one day, she said to me,

“Papa, I made a song. I’ll sing it, so listen, okay?”

I replied, “Sing it! Papa will write it down in his notebook,” and she began to sing.

“When I was in Mama’s tummy

Mama always said, ‘Do your best, do your best’

Mama’s tummy was warm

Thank you, Mama

When I was in Mama’s tummy

Papa always said, ‘Do your best, do your best’

Papa’s voice was loud

Papa, you were noisy.”

She sang it over and over, laughing each time. Strangely, the melody was different each time, but the lyrics never changed.

I still remember it like it was yesterday—how touched I was that she even made a song about me. Tears welled up in my eyes. That night, as I watched her sleeping face, I wrote a song in response.

The first time I held you

Papa cried and cried

Poor thing, you look just like Papa

I wished you’d look a little more like Mama

Papa cried and cried

The truth is, the truth is, I was so happy

So happy you looked just like Papa

A story of Papa and you

A story Mama doesn’t know

The day I gave you your name

Papa looked at the moon alone

Papa cried and cried

Before I knew it, I had written up to the fourth verse.

Time flies like an arrow. It’s been twenty-five years—a quarter of a century—since then. She’s probably forgotten all about it by now.

Comment from the Oyako Day Editorial Office: The author also sent us the songs♪

When I Was in Mama’s Tummy

Vocals by: Kyoko Oda

The Story of Papa and You

Vocals by: Kanabun Yamada

DAC NIKI Hills Prize

- Fruity Weekend 100% Juice 720ml 2-bottle gift set

I’ve never seen my mother’s back.

Whenever she was doing something for me, she was facing me.

When she was thinking about the family, I only saw her in profile.

Those were the only two angles I ever saw of her.

I never once saw her acting freely, thinking only of herself.

Perhaps it’s because we were a single-parent household.

My mother divorced before I was old enough to understand.

In addition to our financial situation, I believe a lingering sense of guilt over how things had turned out constantly held her back emotionally.

When I was in high school, my grandfather—who lived with us—had a stroke, and home care began.

There were limits to what my grandmother could do.

Until my grandfather passed away nearly ten years later, my mother couldn’t take a single trip.

Even on the rare occasions when she could meet her friends—maybe once a year—she always made sure to return by 10 p.m.

Every morning, she was up by 5 am to make my lunch and to take care of my grandfather.

Since I always woke up right before leaving for school, I never saw her back.

I would just grab the lunch she had left on the table, say “Good morning,” and head out the door.

From the time I was born until now, my mother has lived her life always thinking of someone else and I, in turn, have lived my life relying on that.

I’ve always tried to be mindful not to cause her trouble, yet I’ve walked through life freely and as I pleased.

From now on, I want to help her live more freely.

I want to see her—forgetting about me and everyone else—running off somewhere with the carefree steps of a young girl.

I want to burn that image of her back into my memory.

Her spirit of selfless dedication—

That, I believe, is what she’s been telling me all along…with the back she never showed me.

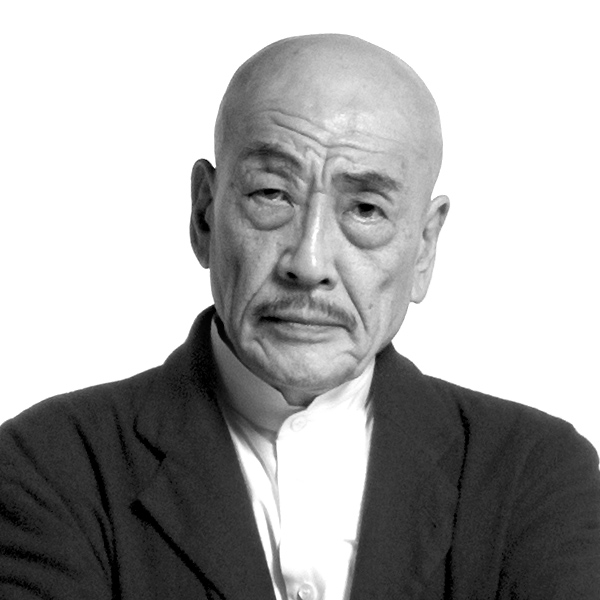

CHOYA Prizes

- Gold Edition

My father passed away from stomach cancer at the age of 53.

I was 17 that summer, so it’s been over half a century now.

He had left the railroad company where he worked before turning 50 due to strained interpersonal relationships.

Thanks to an introduction from my brother-in-law, he was able to find a job collecting payments for a power company.

He was naturally a serious and sincere man, so the job seemed to suit him well.

One evening after dinner, he said, “Hey, look what I’ve got,” and placed a large coin on the low dining table.

“Wow! That’s the Olympic 1,000 yen silver coin!”

My mother was astonished and he explained, “An elderly woman at one of the houses I collect from didn’t have a 1,000 yen bill on hand, so she gave me this instead.”

It became clear that he had immediately exchanged it with his own 1,000 yen bill and brought the commemorative coin home for the family.

“Wasn’t that coin probably a treasure to her?” my sister said.

“She probably got scolded by her family afterward,” added my mother.

My father’s expression changed.

He had thought everyone would be delighted, but now he seemed to feel as though he was being blamed. The cheerful mood in the living room suddenly grew heavy. Only I, a grade-schooler at the time, remained excited—flipping the coin over and holding it up to the fluorescent light.

“If that’s how it is, I’ll return it tomorrow,” my father said, slipping the silver coin into his wallet. His profile looked lonely. It’s a distant memory now, but whenever the Olympics approach, that moment comes back to me. I’ve long since surpassed the age my father was when he passed away. I have a family of my own now, children of my own, and I’ve come to know the joy of gathering around the table with loved ones. I understand now—almost painfully—how my father must have felt at that time. He just wanted to see everyone smile.

CHOYA Prizes

- The CHOYA Gift Edition

That day was my eldest son’s 12th birthday.

I finished work on time and hurried home to my family, who were waiting for me. His requested birthday present was already prepared.

But somehow, it didn’t feel quite right to show up empty-handed on the day itself—so I decided to pick up an extra gift at the bookstore near our house, hoping to make it a bit more dramatic.

Knowing he liked books related to games where monsters evolve and grow, I browsed the shelves for something fitting. As I wandered the store, I suddenly heard my son’s name from the other side of a shelf. His name is fairly unique—there’s no one else with it in his grade—so I was certain the voice was referring to him. Peeking through the shelves, I saw a group of three upper-grade elementary school boys whispering and calling out my son’s name again.

“Could it be… is my son being bullied at school?” I wondered uneasily, hiding in the shadows of the shelf to observe them. “Don’t tell me they’re planning to shoplift?” I listened closely for a while, but found no signs of bullying or theft.

Eventually, the three boys picked up a soccer magazine, paid for it, and left the store. Even so, my unease didn’t go away. I bought the game-related book, had it gift-wrapped, and returned home.

When I got back, my son’s face lit up with joy as he saw his presents: his original gift, a handmade cake from my wife, and the bonus book. My younger son, three years his junior, was equally ecstatic about a little “extra” gift he received too.

CHOYA Prizes

- Ume Shibori Juice (1 case)

My son, perhaps because he is an only child, was never fond of competition and rarely asked for things.

Even when he did want something, the adults around him would eagerly grant his wishes, so he never really needed to assert himself strongly to get what he wanted.

When he reached his final year of kindergarten, the school announced a special overnight event for the Tanabata festival.

We went over the list of items needed, provided by the school, and packed his backpack together.

His face showed a mix of small anxieties and great excitement—it would be his first sleepover away from home.

The parents’ association was planning to set up a mock “festival” with little stalls, and we were instructed to give our children 500 yen as spending money—specifically, five 10-yen coins, three 50-yen coins, and three 100-yen coins—in a small purse worn around the neck.

It would be his first night away from us, and his first time shopping by himself.

For him, it was a tiny summer adventure.

The next day, I went to pick him up, half-worried—Did he wet the bed?—but when I saw him standing a little taller than usual, I knew he had enjoyed himself, and I felt relieved.

With sparkling eyes, he began to tell me all about it.

“Before shopping time started, the teacher took us to the festival classroom and showed us what was there. That way we wouldn’t get confused when it was time to buy things. And when it started, I ran to the stall so I wouldn’t lose to the girls!”

I wanted to ask him all kinds of questions, but I held back, waiting for him to tell the story in his own order.

Before even saying what he bought, he reached into his backpack and placed his first-ever purchase in my hand.

It was a slightly heavy, pink necklace.

“They asked me, ‘Are you sure that’s what you want?’ And I said, ‘It’s a souvenir for my mom,’ and they told me, ‘How wonderful!’ I used the rest of the money to buy some sweets!”

There he stood, holding out that pink necklace—his trophy from his very first competitive moment.

In my eyes, he was a tiny knight, and that image of him is etched forever in my heart.

Mainichi Newspaper Prize

- MOTTAINAI Campaign Goods

Maybe it was because I had turned twenty, or maybe it was because my older sister had just started her first year working and begun living on her own, but my mother started opening up about parts of the past I had never known.

My father, who had inherited and was running a family business that had been passed down since my great-grandfather’s time, was being pressured by his parents to produce a male heir. But after my sister was born, and then I came along, my mother experienced two miscarriages.

As she grew older, concerns about late-age childbirth began to grow. When she was over forty, my father apparently said to her, “It’s okay, we don’t need a boy.”

Still, my mother had left her job upon marriage and joined the family. The unspoken expectation of bearing a son from a different father—my grandfather—had become a heavy burden.

Alone, she knocked on the door of a shabby apartment in Shinjuku, where a blind fortune-teller was waiting.

She asked, “Will I be able to give birth to a boy?”

The fortune-teller told her:

“You two are nothing alike in terms of hobbies or personality, yet you always make decisions at the same timing. That’s a wonderful thing.

I see two adorable little girls riding in a handcart. The two of you are turning equally sized wheels at the same speed, and the girls are bouncing along happily, ‘yo-tto-to, yo-tto-to,’ enjoying the ride.”

It was then, my mother said, that she finally felt at peace—realizing that having two daughters was enough.

I had never known about her miscarriages, or that she once longed for a son.

In a family, there are many moments when big decisions must be made.

With two daughters, the financial burden alone is doubled.

And yet, despite having to constantly make one decision after another, I’ve never once seen my parents clash or grow distant from each other.

Two years ago, my father made a clean decision to close his company during the economic downturn caused by COVID.

Now, he enjoys gardening, photography, and mountain climbing—fully embracing his hobbies.

My mother lets him do as he pleases and leads a laid-back life.

They’ve become a pair that can weather anything.

Someday, when I find someone I truly want to marry, I want to show him to my mother first and really listen to what she has to say.

I want to learn her secret—how to keep the cart moving forward, no matter the road, no matter the storm.

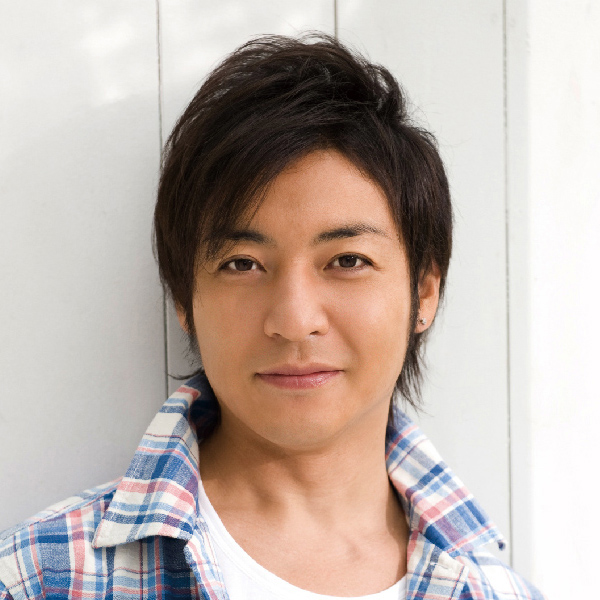

It came like a shock.

“Mom, from today on, can you wait for me behind the next utility pole—not right in front of the cram school?”

“Huh? Why?”

“Just… please.”

At the time, my son was in fifth grade. I had been picking him up and dropping him off at cram school. In fact, I’d even gone so far as to buy a compact European car—a two-seater “S”—specifically for that purpose. The narrow alley in front of the cram school was crowded with children, and I thought my husband’s large RV was far too bulky and dangerous to navigate there. In contrast, the small but sturdy “S” seemed perfect for the job.

But then, one day, my son emerged from the school and practically dove into the car, crouching low as he said, “Hurry, let’s go.”

When I asked, “What’s wrong with the car?” he replied:

“It’s weird. And the fact that you come pick me up… that’s what’s wrong.”

Apparently, some of his friends had teased him.

From that day on, he stopped walking with me. Even when we went shopping for clothes, he insisted on “meet there, leave there” arrangements.

“Let’s meet at that shop on the second floor of Aeon at 10:30,” he’d say.

And once the shopping was done, he’d casually part with:

“Thanks. I’ll go from here,” before heading back to the same home we shared.

“Is this rebellion? Puberty? What even is this?”

I sighed and asked my fellow mom friends.

“Oh, that’s nothing. Mine says I’m ‘annoying’ and ‘gross,’” one laughed.

“What should I do?”

“Just leave him be. If a boy stays clingy to his mom forever, that’s more of a concern.”

Fair point.

From then on, even when my son cold-shouldered me, I kept telling myself: “It’s a sign of growth. Just a sign of growth.”

So, when he was in high school and one day said, “Can you drive me to the outlet mall?”

I was so shocked I blurted out in a goofy voice: “Wh-why, yes, of course!”

He looked a bit embarrassed and said: “Yeah… please.”

Now, my son—who made it through his rebellious phase and grew into a fine young man—is getting married this October. He’s found a wonderful partner, and he’s absolutely glowing with happiness.

They’re about to begin their own family story.

Congratulations, my dear.

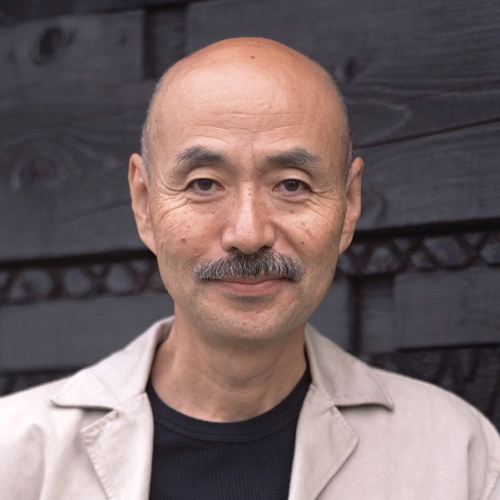

I used to think the two fathers in my life couldn’t be more different.

I was raised by a man who could have stepped straight out of a textbook on stern, old-school Japanese fatherhood. He was strict, yes—but he gave me everything I needed and never let me feel deprived. He never missed cheering at my club games and drove me to and from high school every day. Most of my memories with him are centered around sports—playing catch, going for runs. Every summer, during the high school baseball tournaments, the two of us would sit side by side in front of the big TV in the living room and watch the games together.

It wasn’t just a good balance of closeness and distance—if anything, I was doted on.

Then came the other “father”—my father-in-law, whom I met after getting married.

He’s a great cook, loves to clean, never forgets to take out the trash, and gets along easily with my son’s friends. He’s the total opposite of my own father: gentle, soft-spoken, and warm. When his first grandchild was born, he beamed with pride and happily helped take care of the baby. He takes walks every day with his grandchild and his beloved dog. He’s the epitome of the kind, peaceful countryside grandpa.

At first glance, they seem completely opposite—but in truth, they’re surprisingly alike.

To put it kindly, they both live with conviction, following their own path with unwavering love for themselves. Less kindly, they’re incredibly stubborn and a little self-centered.

My father spends his days off practicing softball with his local team and drinks as much as he pleases every day. He pours his time and money into the things he loves.

My father-in-law? Fishing. The shoreline isn’t enough for him—he boards boats and heads out to sea. He, too, spares no time or money for his passion.

Watching the backs of these two men, I couldn’t help but feel a bit envious. Part of me wants them to change, and another part wants them to stay exactly as they are.

They’re like boys who just happened to grow old.

Strange and endearing, these two fathers of mine.

My husband is steadily growing into the image of them both.

And I wonder—will our child one day follow in their footsteps too?

Whatever the case, I’m proud to call them both my fathers.

Tsuburaya Productions Prize

- Ultraman Blazer THE MOVIE: “Giant Monsters Clash in the Capital” Blu-ray Special Limited Edition

As a working mom, the walk home from daycare is the most exciting time of my day.

Once we get home, it’s a whirlwind of dinner prep, bath time, and bedtime—leaving little space for a relaxed conversation with my son.

That’s why this walk home is so precious to me.

The walk would only take ten minutes at an adult’s pace, but with my three-year-old, it becomes a leisurely 15 to 20-minute stroll. During that time, I get to experience a whole spectrum of emotions from him—cute, funny, and sometimes, let’s be honest, exhausting.

My car-loving son watches the traffic and excitedly points out, “That one’s cool!” or “That car’s pretty rare!”

If a firetruck or police car passes by, we both exclaim, “Lucky!” and cheer together.

In summer, we search for cicadas; in winter, we admire holiday lights and snap selfies together like we’re on a date.

During his “stair phase” (every kid has one, right?), I would just stand by and watch as he climbed up and down the steps on our route over and over.

When he had just turned two, he suddenly said one day, “Shall we go shopping at the milkman’s?” as we walked our usual path.

The milkman? I followed his gaze and saw the familiar blue sign of a certain convenience store.

Sure enough, there was a little milk can logo on the sign, and I couldn’t help but laugh.

But then I wondered—how did a Reiwa-era child even know what a milk can was?

I asked him, “How do you know that’s milk?” but, as expected, got no clear answer. He was two, after all.

Since then, that store has forever been “the milkman’s” to us.

In just a few more years, he’ll be in elementary school, and we probably won’t walk hand-in-hand like this anymore.

That thought makes this time feel even more precious.

Sure, there are evenings when I’d love nothing more than to plop him into the bike seat and speed home.

But for now, I want to savor this fleeting, irreplaceable time with him just a little longer.

OYAKO DAY Prize

- Oyako Day Special Gift Set

Lately, my 92-year-old grandma’s forgetfulness has gotten much worse. She remembers her wartime experiences and youth with astonishing clarity.

Her long-term memory is still sharp, but her short-term memory has become incredibly fragile. Watching her decline day by day is heartbreaking.

She often says to my mom, “What was it again? I just can’t remember anymore,” when trying to recall how she spent her day or whether she took her medicine properly.

I’m short-tempered, and I sometimes find myself getting irritated with her.

But my mom gently reassures her: “Yes, you took your medicine—I saw you,” or “The helper came today, remember? How was that?”

I once vented to my mom, “You’re amazing. I don’t mind dealing with dementia patients at work, but spending the whole day with Grandma on my day off drives me crazy.”

She replied, “It’s not like I don’t feel anything either. I get frustrated too. But Grandma doesn’t forget things on purpose. It would be cruel to blame her for that.”

Maybe it’s the difference between a daughter and a granddaughter—the way we perceive things, the way we feel.

Lately, though, my mom has started saying things like “What should I do? I don’t know,” or “I’ve forgotten again…”

And I think to myself—Ah, the time has come for Mom too.

Being together can be frustrating at times.

But it also brings joy—going on trips, sharing delicious meals even though her appetite is fading.

It’s okay to forget. It’s okay not to understand.

Let’s just stay together.

Because you are someone I love.

“You’re a good child. Stay well today, too.”

This was part of my mother’s daily routine—stopping her walker on her way home from her morning walk

to greet the Jizō statue that stood at the entrance of the elementary school in front of our house.

Whenever she encountered a Jizō statue during her travels, she would gently pat its head and speak to it as if reuniting with a long-lost child.

She would wash the weather-worn statues, faded from rain and sunlight, and carefully dress them with red caps and bibs that she had sewn stitch by stitch.

She prayed for the health and safety of her children living far away—something she only recently told me.

I now realize that, by entrusting her children’s well-being to these statues as they left her side, she was also filling the emptiness in her own heart.

The many photos I have of my mother standing next to Jizō statues across Japan vividly bring back memories of our travels together.

As the years passed, my mother’s expression grew gentler, more serene—just like the Jizō statues beside her—and even more beautiful.

It was as if the hardships she had endured throughout her life had nourished her soul and deepened her grace.

Today, my 92-year-old mother lives in a care facility and the Jizō statues are no longer part of her daily life.

While I wondered what might fill that void, she once surprised me during a visit:

“Look at this!” she said, unbuttoning the chest of her blouse to reveal a small, rolled-up piece of thick white paper that she had made herself from hand-wiping tissue.

I was in sixth grade when my father—who had left our family—sent me a VHS tape of a movie.

At the time, I was obsessed with Jackie Chan and Dragon Ball, and had never watched a Western film. I couldn’t understand why he had chosen to send me that tape,

but it became the first foreign movie I ever saw—with subtitles.

Later, when I was in junior high, my father said to me, “Let’s go to America together during summer break.”

He took me not once, but twice—once during summer vacation and once during winter break.

It’s not like he had money. After leaving the family, he started from nothing.

He worked the assembly line at a car factory, tightening hundreds of bolts a day—so many his finger joints bent from the strain. He worked night shifts,

lived in a dorm, and saved every yen to be able to take me on those trips.

Of all the places we went, New York left the deepest impression on me.

He handed me $20 and simply said, “Be back at the hotel before sundown.”

Then I explored the city by myself on $1 buses.

Intersections.

Traffic lights.

Graffiti.

Homeless people.

Yellow cabs.

The Statue of Liberty, barely visible in the distance, no bigger than my pinky finger.

It felt like I had wandered into the world of a movie.

In New York, everyone you see breathing the same air—including me—is undeniably a New Yorker.

Not Japanese, not Asian, not white, not Black—just people, with no borders between them.

That spirit of openness is what New York gave me.

Back when I was still single, before I got married, I once went on a day trip with my father. We were trying out a method for boosting our luck that a

fortune-teller had told me about: take a trip in a lucky direction. Coincidentally, my father had the same lucky direction, so we decided to go together.

Our destination was Katsuura, in Chiba Prefecture. After enjoying a meal at a seafood restaurant near the fishing port, we visited Tanjō-ji, the temple

where the monk Nichiren was born. As we stood looking at the map by the entrance, I noticed a small building labeled Ota-dō—Ota Hall—tucked in the

corner. My maiden name is Ota, so I couldn’t help exclaiming, “It’s Ota Hall!”

My father pointed to the little illustration of the building and said, “That’s where our ancestors are.”

He added, “A relative who lives nearby takes care of it.”

I was surprised, of course, but we didn’t actually visit the hall—we just headed home.

Years later, after I got engaged, the memory of Ota Hall came back to me. “I need to tell my ancestors I’m getting married,”

I thought. Normally you’d visit your family grave, but for some reason, Ota Hall was the only place that came to mind.

So this time, I invited my fiancé (now my husband), and the two of us made the trip to Katsuura.

Seeing Ota Hall for the first time, I was taken aback by how small and—if I’m honest—worn down it was. The structure was very old,

with a single small bell hanging in front. We had arrived late in the day, and the sun was already setting. It felt like the kind of place where a ghost might appear.

Still, we bowed respectfully and made our greeting:

“To our ancestors, I wanted to share the news—I’m getting married. This is my fiancé.”

Since we were there, we rang the bell—gong—and snapped a photo in front of the hall, flashing peace signs.

But when the photo was developed, it came out so dark and eerie it looked like something straight out of a collection of ghost stories.

Later, back at home, I told my dad all about our visit while he was reading the newspaper in the living room.

“I went to Ota Hall today,” I said.

He replied, “Huh? Why would you go there?”

“You said our ancestors were there, so I went to report my engagement!”

He slowly put the newspaper down, looked up at me, and said:

“Oh… that? That was a joke.”

I practically fell backward.

Apparently, not everything parents say is to be taken as gospel.

Maybe this was a belated first step toward true independence.

Or maybe—just don’t make weird jokes that don’t make sense.

It’s one of those memories of my father: expressionless like a statue, making dry, unfunny jokes.

In January of this year, my father passed away. He was 81.

I had long regretted that I hadn’t done anything for him while he was alive. He was always so close… and yet…

Now, my memories are filled with one regret after another.

But about six months after his passing, I gradually began to come to terms with those feelings.

Then July arrived.

We began preparing for hatsubon—the first Bon Festival after someone’s death. Since it’s customary in our area for many people to visit your home during hatsubon,

I decided to tidy up my father’s bookshelf—something that had remained untouched since the funeral.

I stepped into his study. It still carried his scent—one I had loved since childhood and from that study, many nostalgic items began to surface.

First were the photographs—so many photos he had taken over the years. My father loved photography. With his trusty Konica camera, he had filled old, faded albums

with snapshots of memories. There were pictures from company trips, family gatherings, everyday moments. Each one labeled in his neat, precise handwriting, noting

when and where they were taken. Those careful notes made the memories even more vivid—and all the more piercing. I found myself saying “How nostalgic…” aloud

again and again.

Next, I uncovered pamphlets, flyers, and newspaper clippings. Ticket stubs from movies we saw as a family. Articles about my father’s achievements. Essays he had written.

These were precious pieces of his life—proof of the way he had lived. It struck me: He must have truly enjoyed his life. All these pieces of his story were thoughtfully stored

together, beautifully organized in boxes.

Finally, I opened a drawer in his desk. Inside, I found the diary he had written in every day. I had known he kept a diary, but I had never once looked inside. Now, curiosity got

the better of me. I opened it and the moment I did, the tears came—and wouldn’t stop.

The pages were filled with entries about me, his eldest son. The day I got married. The day my children—his grandchildren—were born. The outings we took together as a family.

He had carefully recorded all those everyday moments with us. Each entry ended the same way: “Today was another happy day.”

In that moment, I realized how deeply he had loved me—even though I had often felt I was a disappointing son. He had worried about me. And still, he gave me his unwavering love.

The final entry was dated May 15th—the day before he collapsed, on May 16th.

May 15th: “Worked in the garden in the morning. It was hot today. Had dinner with Hiroaki and his family in the evening. Today was another happy day.” It took six months after

his passing for me to truly understand—Just how deeply he loved me, how much care he put into raising me.

Soon, it will be his first Bon Festival. For his sake, I want to show him I’ve become a reliable eldest son.

Now that his study is finally cleaned and organized, I can say it with confidence:

Thank you, Dad.