Text Edition: 19th Online Talk Live with Tetsuya Chiba – “Present to the Future” (Special War Memories)

19th Online Talk Live: “Present to the Future” (Special War Memories)

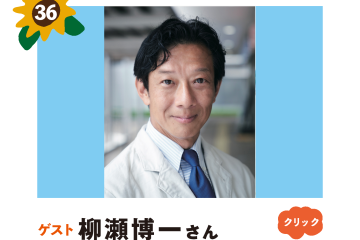

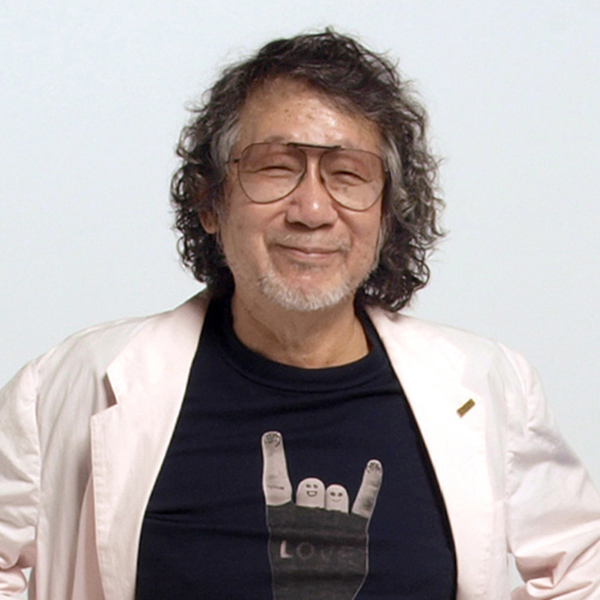

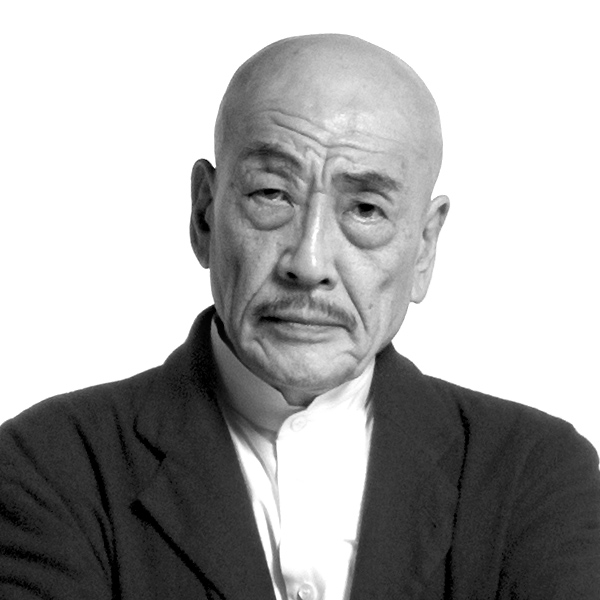

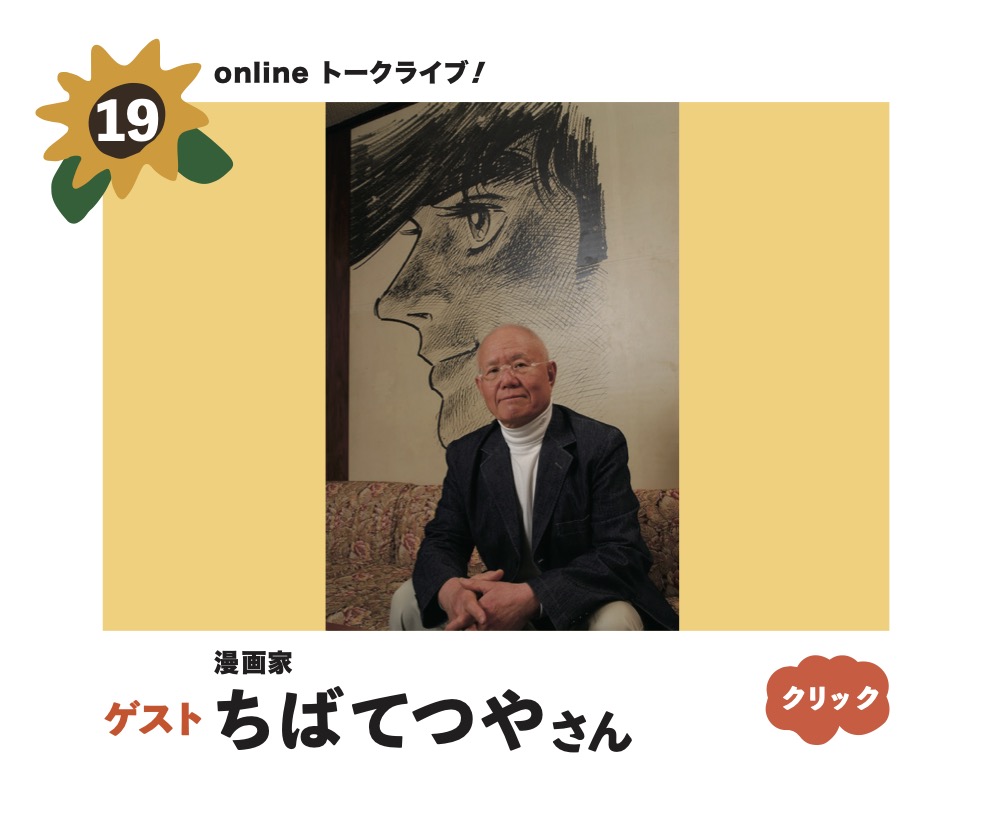

Guest: Tetsuya Chiba (Manga Artist)

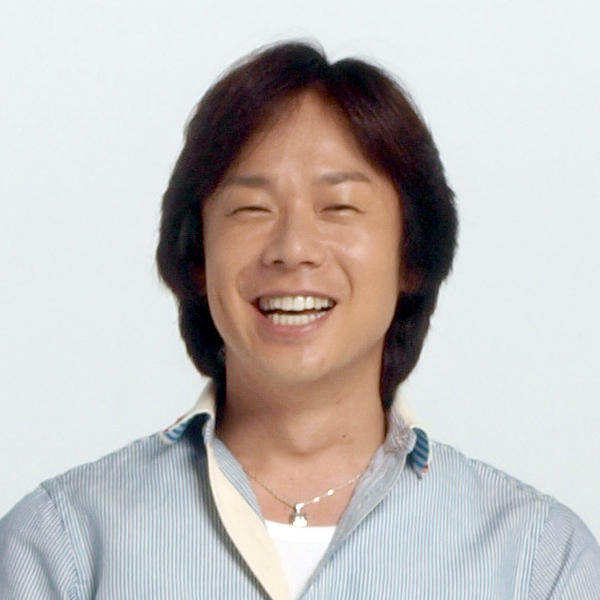

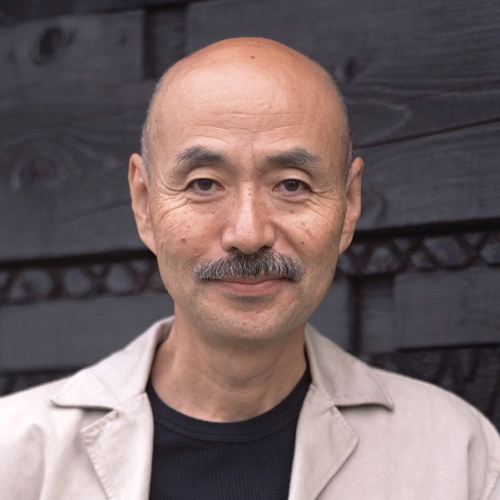

Host: Satoru Seki (Editor/Producer)

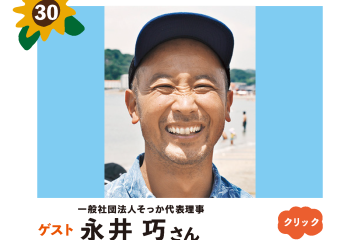

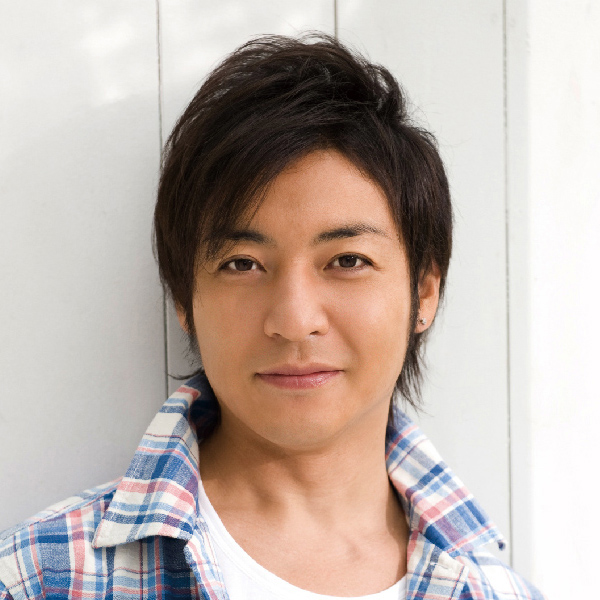

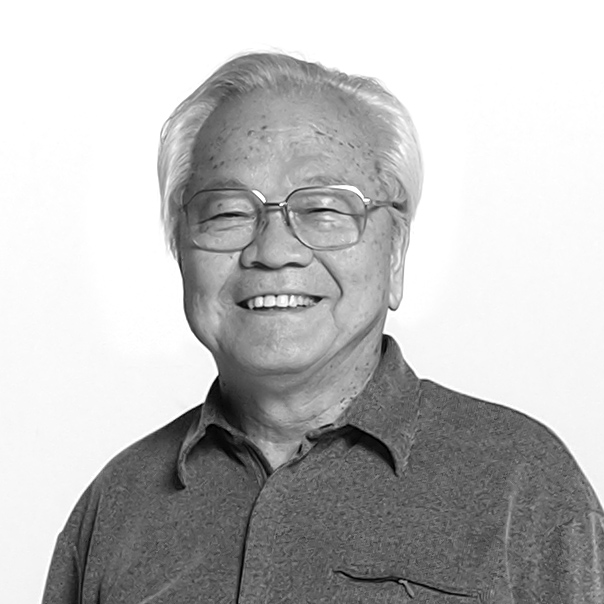

Facilitators: Bruce Osborn (Photographer), Yoshiko Inoue (Oyako Day Promotion Committee)

Organizer: Oyako Day Promotion Committee

Streamed Live: January 21, 2024, 10:00 AM JST

For our 19th Online Talk Live, we welcome legendary manga artist Tetsuya Chiba.

This article presents a full, unedited transcript of Mr. Chiba’s vivid recollections of his wartime childhood, told in his own words and illustrated with his own drawings—just like a live kamishibai (Japanese picture story show).

<Watch the full video here>

Participants:

Tetsuya Chiba (Manga Artist)

Born January 11, 1939, in Tokyo. Lived in Fengtian (now Shenyang, China) during the war, then returned to Japan. Debuted as a professional manga artist in 1956. His most famous works include “Ashita no Joe,” “Notari Matsutaro,” and many others.

Satoru Seki (Editor/Producer)

Worked on culture magazines like “POPEYE,” “BRUTUS,” and “Takarajima.” He is also a part-time lecturer and director of the Stimulus Switch Laboratory, and runs the “Movie Oyako-don” feature on the Oyako Day website.

Bruce Osborn (Photographer, Oyako Day Originator)

Began photographing parents and children in 1982. In 2003, established “Oyako Day” on the fourth Sunday of July. Recipient of the Higashikuninomiya Culture Prize for social activities through Oyako Day. Continues to send out his message, “Present to the Future.”

Yoshiko Inoue (Chair, Oyako Day Promotion Committee; Producer; CEO, Ozone Co.)

Produced numerous exhibitions and events as Bruce Osborn’s partner in both work and life.

Tetsuya Chiba Shares His Wartime Memories

Seki: Welcome to our very first live stream of 2024! Today we’re joined by manga legend Tetsuya Chiba. Thank you so much for being here.

Chiba: Thank you for having me.

Seki: For many of us, your work is a part of our lives. I grew up reading your manga—”Harris no Kaze,” “Ore wa Teppei,” and “Notari Matsutaro”—stories about outsiders struggling and fighting back. These days, we don’t see those kinds of stories as much, so I really want to learn from your spirit of resistance and never giving up.

Childhood in Manchuria: Experiencing the End of the War

Video 13:34 – “The Journey Back to Japan”

Seki: I’d like to start by asking what made you want to become a manga artist. I know you brought some drawings, so could you walk us through your story—starting with your family’s repatriation from Manchuria?

Chiba: This is the part of Manchuria where we lived, in northeastern China. See the area outlined in red? Doesn’t it look like a bird taking flight? When I was a child, my parents told me, “This is where we live,” and I thought, “It looks like a bird in the sky.” We lived around the “leg” of the bird, near Fengtian—now called Shenyang. Although I was born in Tokyo, my parents moved to China for work when I was little, so I grew up there until I was six years old.

Seki: So you experienced the end of the war at six. That must have changed everything.

Chiba: We actually had a good life there. My father worked at a printing factory, and we lived in company housing behind high concrete walls—everyone around us was either a colleague or family. But when the war ended, everything changed. Suddenly, “This is Chinese land now,” we were told. The factory, the houses—everything that was Japanese was taken away or transferred to the Chinese. We had to flee back to Japan, but it wasn’t easy.

Memories of Manchuria

Video 15:18 – “Tanghulu, the Candy of Manchuria”

Chiba: What you see here is tanghulu—a local treat from Manchuria. It’s a skewer of little crabapples, coated in syrup that freezes and cracks when you bite it. The candy is sweet and the fruit is tart inside. Even today, you can still find street vendors selling tanghulu in China in the wintertime. I loved them.

Chiba: That’s my younger brother in the picture too, holding his own tanghulu. I always had a bit of a wanderer’s spirit—despite living in the factory compound, I was always sneaking out to explore the city, even if it meant getting lost. The Chinese townspeople were very kind. There were plenty of Japanese kids and lots of stalls selling things like steamed buns or birds. I got treats from all kinds of people.

Seki: So you have some really good memories from that time?

“We Might Be Separated”—The Family Photo Taken in a Hurry

Video 17:30 – “Our Family Photo”

Chiba: See how battered this photo is? There are creases everywhere. I’m amazed we managed to bring it home. There are four boys here—my brothers and me. I’m the eldest, just left of center with the big forehead. The one being held by my father is my brother Akio, who also became a manga artist. The youngest, Shigeyuki, is in our mother’s arms. When this was taken, things were tense—Japan had likely lost the war, and my father was in danger of being drafted. My parents hurried to take this photo, thinking we might soon be separated forever. It got battered as we carried it through all our travels, but somehow we held onto it.

Video 19:09 – “Chinese Friends Who Helped Us”

Chiba: This is my father with one of his Chinese friends. He was the type who could get along with anyone—Chinese, Mongolian, Korean, it didn’t matter. They’d all share meals at our house. Later, it was these friendships that helped save our family. Looking back, I’m grateful for how important those relationships were.

The Night the Emperor’s Speech Was Broadcast—And an Attack

Video 19:51 – “The Day of Surrender”

Chiba: This drawing shows the printing factory compound where we lived. That day—August 15th—we were all called to the manager’s office. We listened to the Emperor’s radio broadcast announcing Japan’s surrender. I still remember the cicadas singing in the summer heat and the sight of the grown women crying.

Seki: This is a really moving drawing.

Chiba: I drew it from memory. That night, the sky glowed red with dust—maybe it was the famous yellow dust storms of China. As I watched the sunset, a group of people climbed over the high wall into our compound. They carried sticks and clubs. It was a riot—many Chinese and Korean people, angry at how the Japanese had lorded over them during the occupation, came to seek revenge. I remember thinking I saw familiar faces, friends of my father’s, but my mother grabbed me and said, “Tetsu, get inside!” Our house wasn’t touched, but I heard the sounds of windows breaking and people screaming nearby. It was frightening.

Video 21:18 – “Riots Break Out”

Escaping by Night—Our Family on the Run

Video 23:03 – “Packing for the Escape”

Chiba: Not long after, we realized we couldn’t stay. We packed everything—old photos, baby supplies, anything essential—into bags. Because of the danger, we could only travel at night. At midnight, we snuck out the back gate and started our escape.

Video 23:58 – “Sneaking Away at Night”

Chiba: This scene shows us walking through the darkness. I was so tired I was half asleep.

Video 24:44 – “The Six of Us Escaping Together”

Chiba: There are six of us: my father carrying Akio on his shoulders, my mother carrying the youngest, and me holding my father’s hand, half-asleep. Even today, many people around the world are fleeing wars, forced to leave their homes just like we did nearly 80 years ago.

Saved by My Father’s Chinese Friend

Video 25:55 – “My Father’s Friend”

Chiba: There was a time when I got separated from my family because my feet were bleeding and I couldn’t walk. Suddenly, a man in a conical hat appeared, carrying a long stick. I was terrified—he might attack us. But it turned out to be one of my father’s old Chinese friends. We’d shared meals, books, and poetry together. In that vast city, to run into him—especially in the middle of the night, while I was lost and desperate—was nothing short of a miracle. Thanks to him, all six of us were safely reunited.

Video 27:18 – “Hiding in an Attic”

Chiba: We stayed at his house for a while. Space was tight, so we hid in the attic, which was usually used for storing onions and potatoes—though there was no food left in those days. We hid there until it was safe to move again.

How I Became a Manga Artist: The Origins

Seki: You were drawing even back then?

Chiba: My younger brothers were restless, wanting to go outside—especially when they could hear Chinese children playing. To keep them quiet, I drew pictures on whatever scraps of paper I could find and told them stories, like a one-boy kamishibai. I didn’t realize it then, but that was the beginning of my life as a storyteller and manga artist.

My mother later said, “Remember when you drew pictures for your brothers in that attic? That’s probably where it all started.” Wanting to entertain my brothers, to keep them from getting bored, became a part of who I am as a creator.

Video 30:19 – “Peddling Goods to Survive”

Chiba: This is Mr. Xu, my father’s Chinese friend, in the foreground. He taught us how to buy and sell vegetables and other things in the market—how to survive by peddling goods. My father wore a conical hat and pretended to be Chinese so we wouldn’t get in trouble. We sold to Japanese people in hiding, who desperately needed supplies. Whatever didn’t sell, we ate ourselves.

A 300km Trek to the Repatriation Ship

Video 31:40 – “Walking to the Repatriation Ship”

Chiba: This drawing shows us heading toward the port to catch the ship back to Japan. Off in the distance, you can see a railroad embankment. We wanted to take the train, but all the trains were taken by the Chinese army, so we walked almost the entire way. Our hometown was near Fengtian, and we were headed for Huludao Port, which was the closest place we could catch a repatriation ship to Japan.

Video 32:53 – “At the Repatriation Port”

Chiba: This was when we finally reached the port. It took almost a year—by then I was seven. People had come from even further north, and everyone was exhausted.

Video 34:00 – “Waiting for the Ship”

Chiba: Here we are, waiting to board the ship at Huludao. Some families had traveled even farther than ours—300 kilometers or more—just to get here. Everyone was tired and worn out, but at last, there was hope.

Video 34:39 – “Hardtack and Soup on the Ship”

Chiba: On the ship, they gave us rations—hardtack biscuits with holes in them, and a thin soup with a bit of soy sauce and cabbage. After so long surviving on millet and scraps, these simple foods tasted like heaven.

Arrival in Japan—Seeing My Homeland from My Father’s Arms

Video 35:51 – “Arriving in Japan”

Chiba: When the ship finally reached Japan—Hakata Port—someone shouted, “Japan is in sight!” and we all rushed to the deck. My father lifted me up in his arms so I could see our homeland. It had taken us a year since the end of the war to return home.

Video 36:54 – “Returning to My Father’s Hometown”

Chiba: When we reached my father’s hometown, we arrived late at night and knocked on my grandmother’s door. She didn’t open up at first, but when she realized who it was—her son Masaya and his family, now with four kids—she was so surprised she could hardly believe it.

Video 38:51 – “Life in Mukojima”

Chiba: We stayed with family for a while. Later, my father got a job in Tokyo and built a small house in Mukojima, Sumida ward. That’s me in the drawing with the shaved head, surrounded by my brothers and neighborhood kids.

Discovering Manga in Elementary School

Video 39:28 – “Elementary School in Chiba Prefecture”

Chiba: After we came back, I started elementary school in Chiba prefecture. Classes were crowded, and sometimes we had to attend in shifts. When we moved to Tokyo, I met a boy named Kiyuchi, the son of a Buddhist priest. He was big, and I was small, but he drew manga. Until then, I didn’t even know manga existed. I’d seen picture books, but not comics. Kiyuchi would peek at my drawings and say, “You’re good! Want to draw manga with me?” That was my first exposure to this world, and it was a real culture shock.

The War Didn’t End with Surrender—Hardship Continues

Video 41:58 – “My Parents”

Chiba: Even after we returned, life was still incredibly hard. My parents always gave what little food we had to the children—I never actually saw them eat. My mother even lost her milk from malnutrition, so she would chew up millet and spit it into my youngest brother’s mouth. We all suffered from malnutrition and illness after coming home. Just because the war was over didn’t mean life was suddenly peaceful; the scars lingered for years. Many people died from hunger on the streets. The suffering didn’t end with surrender.

Video 43:59 – “People on the Hill”

Chiba: The weakest—children, women, the elderly, and the sick—were often the first to collapse. Even now, the tragedy of war still feels very real to me.

Seki: It’s important that voices like yours are heard, especially with so many conflicts happening in the world today.

The Importance of Sharing Wartime Memories

Chiba: There are still a few people left who experienced the war firsthand, but most are in their 80s, 90s, or older. Soon there will be no one left to tell these stories. We have to keep passing them on—so people know just how terrible war is. Every war happens because someone profits from it. The ones with power make the decisions, but it’s always the innocent who suffer. We must never forget this, and we must do everything we can to stop it.

Yoshiko: Even today, when a war ends, the pain and scars remain for years. Please keep sharing these memories so we never forget.

Tetsuya Chiba’s “Present to the Future”

Video 50:34 – “Message Board”

Seki: Thank you so much, Mr. Chiba. As we wrap up, could you share a message for the future?

Chiba: I drew this piece as my “gift to the future.” Japan is a country that has survived disasters and war. Now, our athletes bravely compete on the world stage in baseball, soccer, and more—but as a nation, we have a commitment to never again start a war. That’s something I hope all young people will take to heart. That is Japan’s true pride, and it’s my message to future generations.

Seki: Thank you. That’s a message we’ll remember.

Yoshiko: The spirit of Oyako Day is about cherishing the life we receive from our parents and passing it on to the next generation. I’m so grateful you could share your story with us today.

Seki: Thank you so much for spending this time with us.

Chiba: Thank you very much.